William Eggleston may be the closest thing in the world of art photography to a rock star. Not so much a swaggering front man like Mick Jagger or Freddie Mercury, but perhaps more akin to Bob Dylan – an eccentric personality, but nonetheless a driven and prolific artist with a willingness to push the boundaries of his medium and reject popular expectations and commercial pressure. And much like Dylan, Eggleston has become a somewhat legendary figure, surrounded by a great deal of myth and misconception. In Eggleston’s case, I think some of this is due to the scarcity of readily available information, and the resulting proliferation of poorly researched articles that tend to repeat many of the same erroneous assumptions. Much of it is also likely due to Eggleston’s own reticence, his apparent aversion to publicity, and his tendency towards obfuscation in the rare interviews he grants.

All images © William Eggleston except as indicated.

I want to dig a little deeper than the usual popular press articles that appear around every new Eggleston book or exhibition, and investigate the truth behind some of these myths. As with any great artist, I think that much can be learned by a close examination of Eggleston’s process and approach. For me, demystifying some of the legend surrounding Eggleston has led to a deeper appreciation of his work and his contribution to photography. To deal with these misconceptions is not to diminish his value, but rather the opposite; by discarding some of the mythology, we’re reminded that Eggleston, while no doubt incredibly gifted, is hardly a mystical being – or some drunken idiot savant – but in fact a highly intelligent and insightful person who has invested a massive amount of work into his craft, and who has had to make the same types of decisions and solve the same problems that we all do as photographers and artists. And as we’ll find, the truth is far more interesting and inspiring than the myth.

1. William Eggleston and Kodachrome

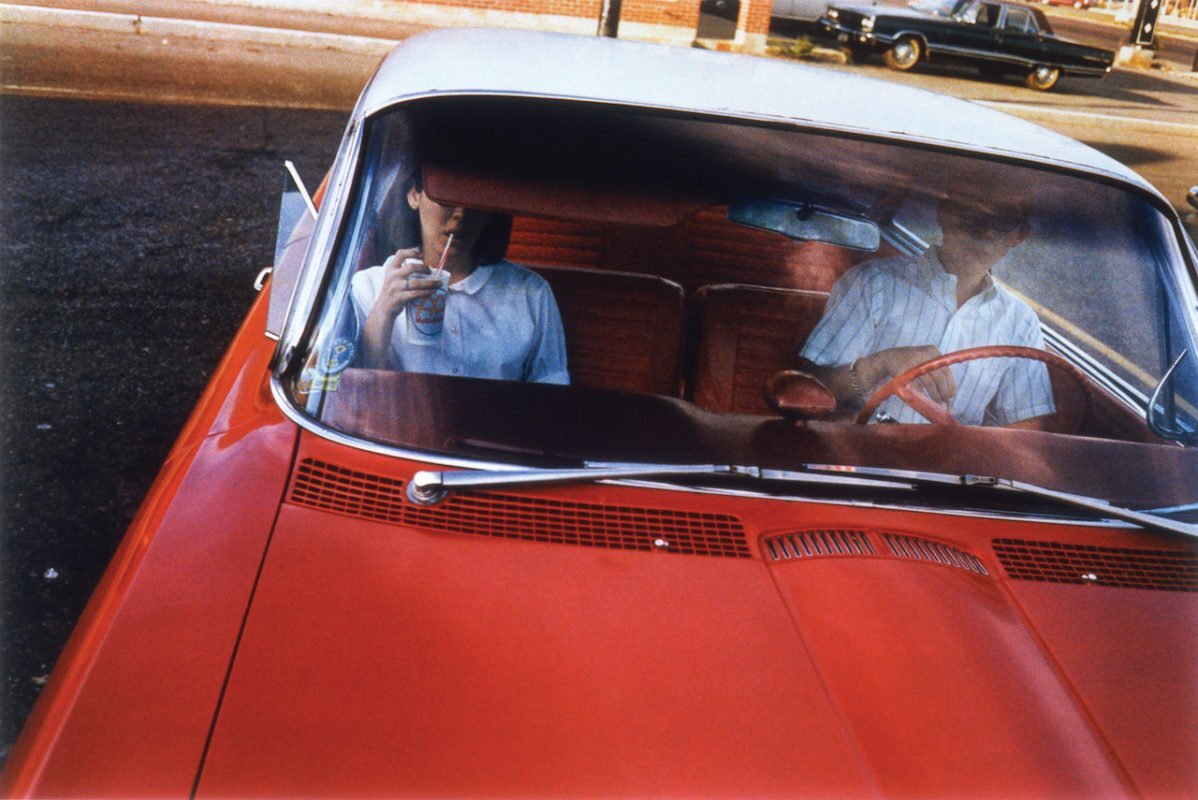

Untitled, Greenwood, Mississippi (1973)

A common misconception is that Eggleston achieved his signature saturated look largely through the use of Kodachrome (1) slide film. Which implies that, since Kodachrome is no longer manufactured or processed, there’s no way to approach the look of an Eggleston photograph with today’s materials.

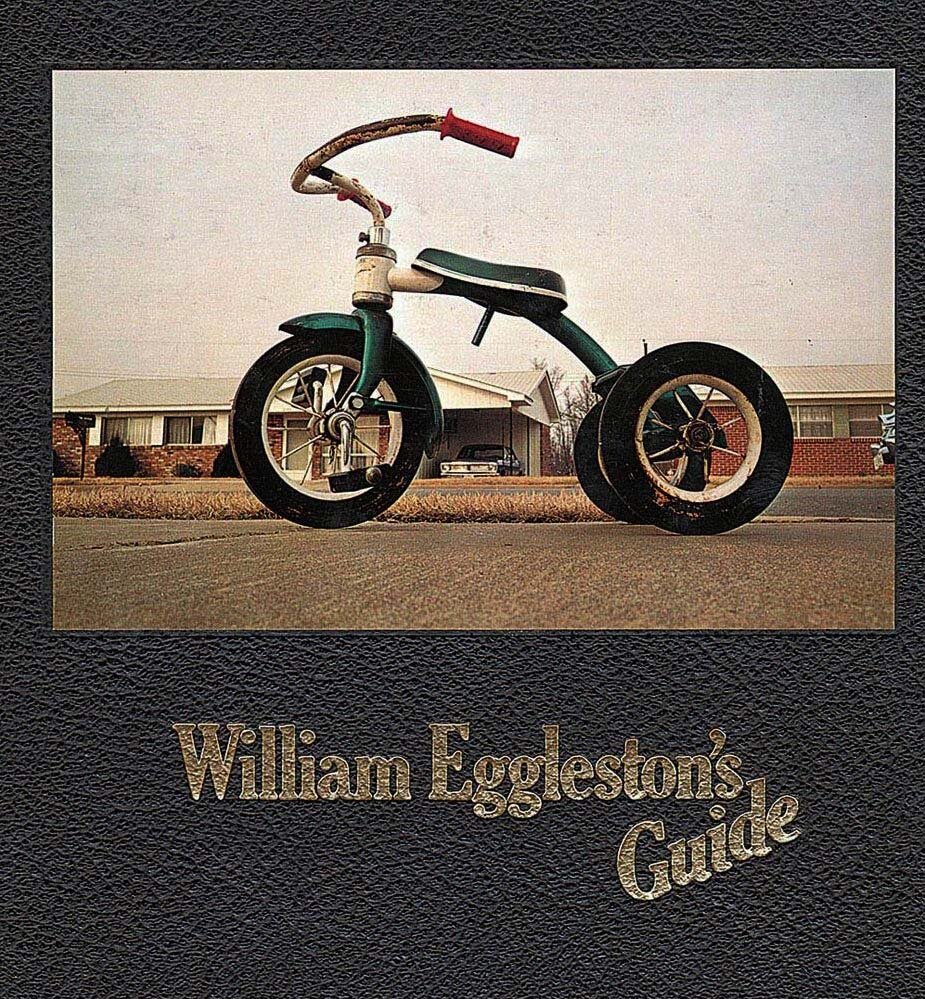

But this is largely untrue. The majority of Eggleston’s well-known work was shot with color negative film. In fact, the only major body of work that Eggleston shot on color transparency film (and even then, not exclusively Kodachrome) is the work created in and around Memphis and Mississippi from approximately 1968-1974 which was published in William Eggleston’s Guide, then later expanded in Chromes.

The origin of this misconception is unclear to me. Perhaps it’s because this 1968-74 body of work comprised Eggleston’s famous 1976 MoMA show and the Guide, which together first introduced Eggleston to the mainstream art world. It may also stem from a simple assumption among photographers today that Kodachrome was the dominant, if not the only, medium for color photography readily available in the 1960s and 70s. But in fact, Kodacolor negative film was available in the 35mm format as early as 1958, and Eggleston began using color negative film in 1965 (2), with some of his first color images surfacing decades later in the body of work now known as Los Alamos.

Eggleston, who had already been photographing in black and white for several years, began using color film after connecting with the artist William Christenberry in 1963 or 1964 when both had arrived in Memphis (3). Eggleston recalled seeing a set of color “drugstore” prints (which could only have been made from color negative film) which Christenberry, primarily a painter and sculptor at that time, created as reference material for his other works.

Eggleston specifically recalled his first attempts with color negative film in an interview, and he identifies the well known photo of a boy pushing shopping carts – which later appeared in Los Alamos – as his first successful color frame, dating to 1965.

Untitled (1965) from Los Alamos

“My first tries were ridiculous. I got some snapshots back, and I hadn’t exposed them properly, they were awful … I’d assumed that I could do in color what I could do in black and white, and I got a swift, harsh lesson. All bones bared. But it had to be. Then one night I stayed up figuring out what I was gonna do the next day, which was go to the big supermarket down the street, then called Montesi’s – why I don’t know. It seemed a good place to try things out. I had this new exposure system in mind, of overexposing the film so all the colors would be there. And by God, it all worked. Just overnight. The first frame, I remember, was a guy pushing grocery carts … those pictures revealed the beauty of light. That it was capturable.” (4)

This type of overexposure could only work with color negative film. And overexposing – in addition to capturing the colors more vividly – likely overcame some of the technical limitations of the film of the era, especially the more prominent grain. Even with modern color negative film, overexposing reduces grain and enhances shadow detail.

But if he was so pleased with the results of negative film, then why the switch to slide film? Again, technical limitations paved the way for artistic innovation.

“I got to one point where I thought I’d really go out on a limb, and I resorted to slides because I couldn’t get any decent prints from negatives at the time. I could have if I’d known more about it.” (5)

Another factor was Eggleston’s exposure around this time to the work of other artists, especially Joel Meyerowitz, who was one of the photographers Eggleston sought out on a trip to New York in 1967 – during which he also met the MoMA curator John Szarkowski, who would eventually be so instrumental to his career.

“I’d done the black and white shopping center series, and the negative color experiment had lasted about a year – frankly, a lot of inspiration for the slide work came from seeing Joel Meyerowitz’s slides in New York.” (6)

Joel Meyerowitz, Girl on a Scooter (1965)

Ironically, Meyerowitz, who started out in color using slide film in 1962-64, had largely switched to black and white during this same period due to the inability to readily make prints from his color work (7). But while Meyerowitz wouldn’t return to using color exclusively until the mid-1970s, he continued to experiment with color throughout this period and would likely have already had a large body of color work to share with Eggleston.

This timeline of Eggleston’s use of transparency versus negative film is confirmed by looking at the resulting work. A close examination of the photographs in the Los Alamos book demonstrates the coarser grain structure typical of color negative film, whereas most of the pictures in the Guide and Chromes have little visible grain and the deep shadows and narrower dynamic range typical of transparency film.

Visible grain in a detail from an image made on negative film from Los Alamos Revisited (1965-74)

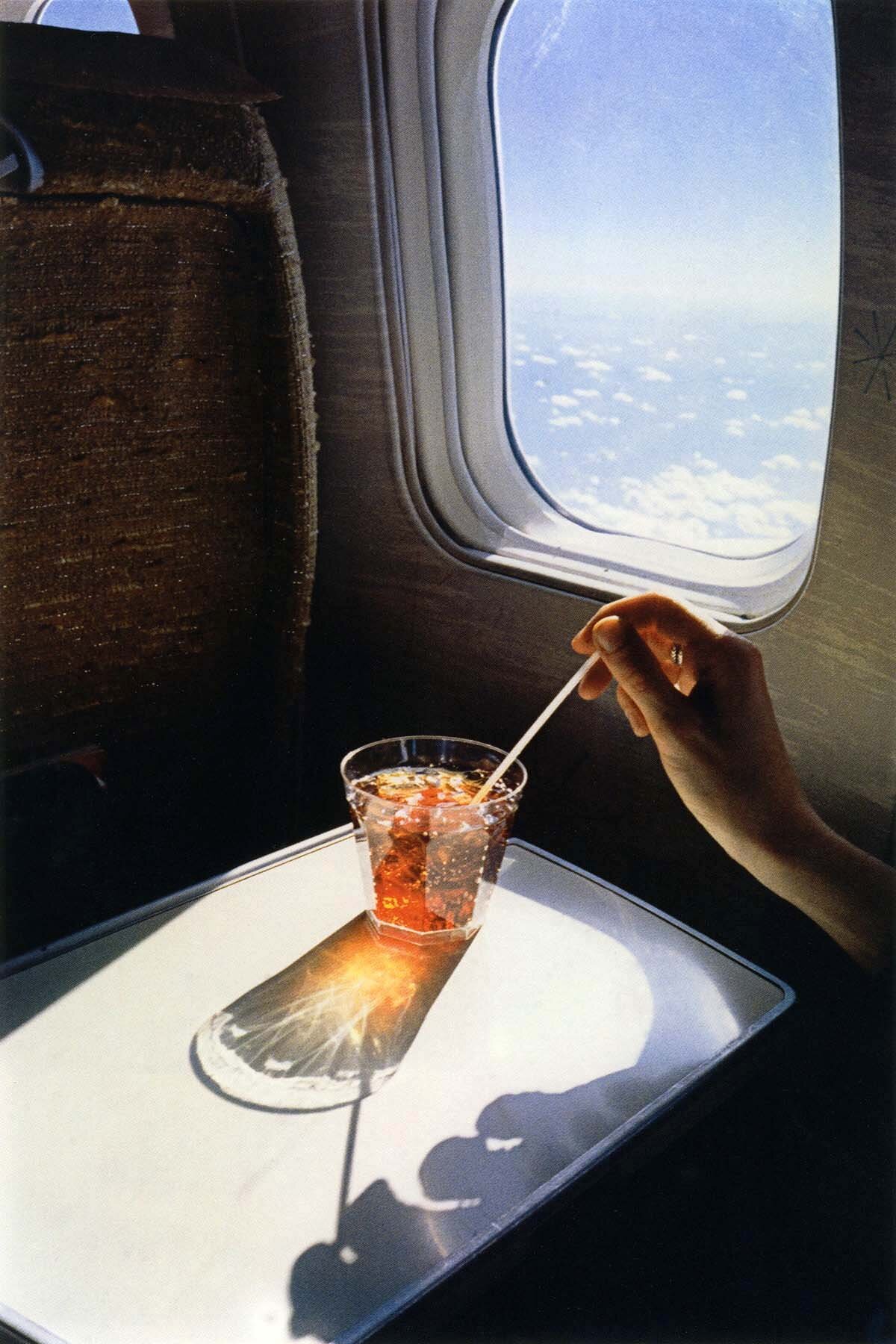

Deep shadows in an image made on transparency film from Chromes (c. 1968-74)

It seems that after the 1968-74 work that would form the Guide and Chromes, Eggleston returned mostly to color negative film for the remainder of his career. Later work such as The Democratic Forest, which occupied much of the 1980s, was also shot with negative film. In a brief interview in the catalog for his 2001 retrospective at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain in Paris, Eggleston confirms,

“Certain images work better with different processes. Kodachrome was the best film and Dye-transfer was the best print you could have made back then, so I used them. Color negative film and C-prints eventually improved greatly so I stopped using Kodachrome.” (8)

So it’s clear that it wasn’t Kodachrome that allowed Eggleston to achieve his signature look. But why does any of this matter? First, Eggleston’s selection of processes – from black and white, to color negative, to transparency, and back to color negative – are a great example of the way that technical advances have always driven artistic progress in photography. Perhaps more than any other fine art medium except cinema, photography has been intimately tied to technology throughout its history. The acceptance and subsequent embrace of color photography by the art world in the mid to late 20th century is a direct result of the technical advances in the medium – particularly the ability to create stable prints from color materials, and the gradually increasing ability of color media to reproduce color more naturally and allow the artist greater control over the color (9).

And Eggleston’s choices regarding photographic media (not just different types of film, but different formats as well) give a glimpse into some of his underlying decision making as an artist, and his efforts towards achieving his vision. He didn’t just rely on whatever was convenient; when a method proved too limiting, he pushed for new options.

Untitled (1965-74) from Los Alamos Revisited

Eggleston’s basic achievement was to employ the tools of vernacular photography (color film, handheld cameras) to create photographs with a seemingly casual, snapshot aesthetic on the surface, but a profound depth and intensity lurking underneath.

"…I had a friend who had a job working nights at a photography lab where they processed snapshots and I'd go visit him because we were both night owls. I started looking at these pictures coming out – they’d come out in a long ribbon – and though most of them were accidents, some of them were absolutely beautiful, and I started spending all night looking at this ribbon of pictures … I started daydreaming about taking a particular kind of picture, because I figured if amateurs working with cheap cameras could do this, I could use good cameras and really come up with something.” (10)

Ultimately, there was nothing really special about Eggleston’s processes. Kodachrome was available in any drugstore. Even dye transfer printing (another process that forms part of the Eggleston myth), while certainly expensive, was used by many other artists. Eggleston’s photographs look the way they do because of him – and, to some degree, because of the places and things he was photographing – not because of what he shot them on.

2. Eggleston is a snapshot photographer

Untitled (c. 1983-86) from The Democratic Forest

I am afraid that there are more people than I can imagine who can go no further than appreciating a picture that is a rectangle with an object in the middle of it, which they can identify. They don't care what is around the object as long as nothing interferes with the object itself, right in the center. Even after the lessons of Winogrand and Friedlander, they don't get it. They respect their work because they are told by respectable institutions that they are important artists, but what they really want to see is a picture with a figure or an object in the middle of it. They want something obvious. The blindness is apparent when someone lets slip the word 'snapshot'. Ignorance can always be covered by 'snapshot'. The word has never had any meaning. I am at war with the obvious. (11)

Although Eggleston clearly employs a snapshot-like aesthetic in his work – making pictures evoking the “beautiful accidents” he found on the night shift at the photo lab – this casual, offhand quality of his photographs lends itself to the misconception that his photographs are actually just casual, offhand snapshots in reality. Even compared to the work of some of his contemporaries also tagged as making “snapshots” – Garry Winogrand’s crowded frames, or Stephen Shore’s diary-like log of food, beds, and toilets – there’s something so outwardly simple about many of Eggleston’s frames that it can be hard for some people to see them as anything more. His pictures feel intuitive. They seem so off-the-cuff that it becomes difficult to imagine any effort going into them. Like a virtuoso musician or athlete, Eggleston makes it look easy – until you try it yourself.

But whereas the casual snapshot photographer merely creates “a rectangle with an object in the middle of it,” Eggleston’s images are driven by composition, color and form. To prove it, turn an Eggleston image upside down. Even though the content – what the photo is “of” – becomes indecipherable, it still works as a pure visual composition, like an abstract painting. It often still evokes a feeling. But most importantly, Eggleston’s work demonstrates intention – he’s deliberate and incisive in his choices, and the resulting images possess a certain power and authority that the amateur snapshot lacks.

Untitled (c. 1968-74) from Chromes (shown here upside down)

“I'd intentionally constructed the pictures to make them look like ordinary snapshots anyone could've taken, and a lot of that had to do with the subject matter – a picture of a shopping center parking lot, for instance. Because the pictures looked so simple, a lot of people didn't notice that the color and form were worked out, that the content came and went where it ought to – that they were more than casual pictures.” (12)

Much like Walker Evans in the 1930s, whose photos used the language of documentary photography to make a new kind of art photograph, Eggleston used not only the technical tools but also the visual language of the amateur snapshot to make a new kind of image. As recounted by Thomas Weski,

When asked if photographs could be documentary as well as works of art, Evans replied “Documentary? That's a very sophisticated and misleading word. And not really clear. You have to have a sophisticated ear to receive that word. The term should be documentary style.” If we try to define William Eggleston's photography with the same precision, we will realize that the critics of his “snapshot photography” were likewise wide of the mark. Eggleston uses the snapshot style, deliberately developing specific patterns of images which seem familiar to us. (13)

Still from William Eggleston In The Real World (2005)

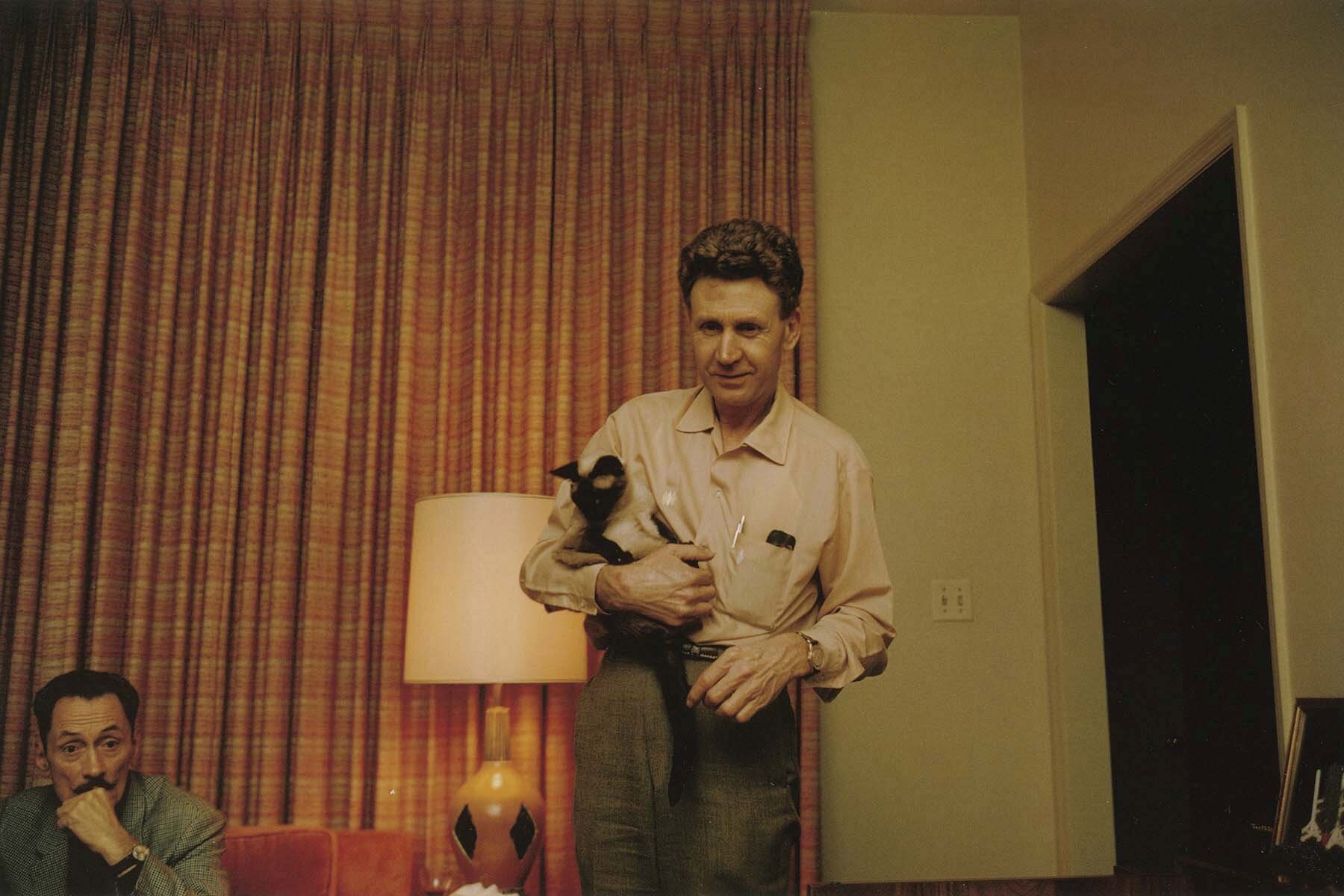

Besides the images themselves, Eggleston’s persona – his laconic manner in interviews juxtaposed with stories of his wild whiskey and Quaalude-driven antics – lends itself to the idea that he’s some kind of intuitive savant who makes pictures with minimal effort. I certainly felt that way the first time I saw Michael Almereyda’s film William Eggleston In The Real World, where it seemed like Eggleston wandered around aimlessly while shooting and had very little to say about his own work. But his inability (or more likely unwillingness) to articulate with words what he does with his pictures shouldn’t be mistaken for a lack of intention or effort.

Because when I re-watched the film again more recently, now with several years of my own photographic experience under my belt, I realized that it demonstrated quite the opposite from what I perceived the first time around: a careful, deliberative photographer who creates images with meticulous attention. In it, we see Eggleston working in a very purposeful and unhurried way, looking at scenes for a long time before picking up the camera, working a scene, evaluating many different angles, making very small adjustments in body placement and framing, and waiting to release the shutter at just the right moment. He may wander like any photographer whose working method involves venturing out into the world without a predetermined plan, but each photograph is made with purpose.

Adding to the “snapshooter” typecasting of Eggleston, at some point he revealed in an interview that he had experimented with shooting without looking through the viewfinder. He likened it to firing a shotgun, with an emphasis on the physical movement:

“It makes you much freer, so you can hold the camera up in the air as if you were ten feet tall. You end up looking more intensely as you walk around. When it is time for you to make the photograph, it's all ready for you. Unlike a rifle, where you carefully aim following a dot or a scope, with a shotgun it's done with feel. You don't look down the barrel and line things up. With a fluid movement your body follows a moving target and the gun keeps moving after the shot with what is known as 'follow through'. That becomes subconscious. Good shooting instructors will encourage you to follow through. It's the opposite of the rational method. When I got the prints from this method, they looked like shotgun pictures.” (14)

In researching this piece, I found that this quotation popped up again and again in articles about him, as if it somehow revealed a secret to his magic. It certainly plays into the popular assumptions about him. And yet, once again, there’s a lot more to it. For someone so attuned towards composition and form, the idea of swinging the camera around haphazardly would make no sense, and simply wouldn’t work. Anyone with even minimal experience in photography – especially the timid beginner who might be tempted to shoot from the hip and avoid bringing the camera to his or her eye in public situations – quickly faces this harsh truth.

Still from William Eggleston In The Real World (2005)

The footage of him in In The Real World immediately disproves that he uses the “shotgun method” most of the time – Eggleston looking through the viewfinder is probably a third of the runtime of the film! I don’t think Eggleston was bluffing – it’s likely he truly experimented with the shotgun method he describes. But I believe that what Eggleston was trying to articulate is a certain physicality in the act of taking a picture that can be less reliant on precise looking through the viewfinder.

There are other examples of this method, especially in street photography, where speed is critical. Garry Winogrand advocated for always looking through the viewfinder, but footage of him shooting demonstrates that the camera was swung across his face in a fluid motion, with the finder often just passing in front of his eye for a brief split-second as the exposure was made. Perhaps an even better example of a photographer using the “shotgun” method is Mark Cohen. He often raises the camera to the subject with a similarly fluid movement, frames without looking through the finder, and follows through just as Eggleston describes.

But the experienced photographer, especially after using only one focal length for a long time, becomes attuned to the camera’s field of view, and eventually doesn’t need to look through the finder to know almost exactly what will be included and where. Ultimately, with this type of approach the photograph is still made with intention and control. “Shotgunning” may introduce an element of chance, and sometimes increase the dynamism and energy of the resulting picture, but it doesn’t make the picture a random accident. As Eggleston himself clarified:

“People say I 'shoot from the hip,' but that's not really how I work," he says. "What happens is, when I look at something it registers on my mind so clearly that I can be loose when I shoot the picture.” (15)

Untitled (c. 1968-74) from Chromes

Untitled (c. 1968-74) from Chromes

Perhaps the best evidence for Eggleston’s approach being quite deliberate comes from a close examination of his work. In particular, the more generous edits made available in Chromes and Los Alamos Revisited reveal many less well-known images that run contrary to the image of Eggleston as a purely intuitive snapshot photographer. There are multiple night scenes which would have required a tripod and long shutter times, many images with subtle use of flash, or a photograph in which his reflection is visible in a car bumper, holding the camera down on the ground in an unnatural location that would have been a deliberate choice, not just the result of casual snapping.

3. Eggleston never took multiple photos of a scene

Untitled (1965-74) from Los Alamos

Alternate version from William Eggleston, Thames & Hudson (2002)

Another related myth that plays into the image of Eggleston as an intuitive, savant-like figure is the idea that he only takes one photograph of each scene. He never needs to “work the scene,” but simply takes the one frame, uses it, and moves on. I blame Eggleston himself for perpetuating this idea in interviews, even though it’s easily disproven.

“Let me put it this way, I work very quickly and that's part of it. I only ever take one picture of one thing. Literally. Never two. So then that picture is taken and then the next one is waiting somewhere else.” Let me get this straight, I say, astonished: each image he has produced is the result of one single shot? He nods. (16)

For a while after first reading that statement, I believed him. It fit right into the myth of Eggleston as a genius. Effortless. But after spending a long time with his books, particularly the Steidl multi-volume editions of Chromes, Los Alamos Revisited, and The Democratic Forest, I started to find many examples of what were clearly the same scenes appearing in multiple photographs. There were never more than two or three images of a particular scene, and usually the angles were varied, but there are surprisingly frequent examples of this even just from the work that’s been published. One retrospective book even includes a nearly identical, but clearly different version (above) of one of his most famous photographs from Los Alamos. While it was probably a mistake, it’s proof positive that Eggleston isn’t above working a scene.

All three images Untitled (c. 1968-74)

There are undoubtedly more among the tens of thousands of prints, contact sheets and slides hidden away at the Eggleston Art Foundation. For example, the full body of work known as The Democratic Forest is said to contain roughly 10,000 images, yet even the massive ten-volume Steidl edition only includes 1,010 of these. And it’s impossible to know how many other exposures Eggleston made at that time which he didn’t use and doesn’t count as part of his finished work. His son Winston has even posted outtakes on his Instagram account.

Untitled (c. 1968-74) from For Now

Untitled (c. 1968-74) from Chromes

Once again, William Eggleston In The Real World also provides some insight. There’s an extended scene in which Eggleston explores an abandoned house in Kentucky. He’s clearly “working the scene,” trying multiple angles and viewpoints. He almost never takes multiple images from exactly the same angle, but what is depicted is certainly not “one picture of one thing.”

But none of this is to say that I think Eggleston is a liar. The reality is a bit more complex. Eggleston himself sheds further light on this topic in the BBC documentary The Colourful Mr. Eggleston; after nearly repeating verbatim the above statement, he elaborates:

“I would take more than one, and get so confused later. I was trying to figure out which was the best frame. I said, ‘this is ridiculous. I’m just going to take one.’” (17)

So what Eggleston is trying to avoid is the perpetual dilemma of the photographer who overshoots – if you have multiple attempts at nearly the same thing, how do you choose? Almost any photographer will know this pain from personal experience – this one or that one? And if neither is better, maybe neither is good at all. It can be incredibly frustrating. So Eggleston makes a conscious choice to avoid this scenario entirely. He may take another picture in the same place, or even of the same object, but it will be different. It’s not that he knows each exposure is so perfect that he can’t better it; instead, he just chooses not to. In a way, it’s a zen approach. Eggleston photographs in the moment. As soon as the picture is made, he lets it go.

And what happens, I ask, if you don't get the picture you want in that one shot? “Then I don't get it,” he answers simply. “I don't really worry if it works out or not. I figure it's not worth worrying about. There's always another picture.” (18)

The point of this isn’t that Eggleston’s approach is necessarily better than the alternative. There are certainly situations when “working a scene” becomes the key to making a great picture. In a dynamic or evolving situation, every frame is bound to be different, and the last might be the best.

All three images Untitled (1965-74) from Los Alamos Revisited

But ultimately, understanding this aspect of Eggleston’s method once again leads to a greater appreciation of his achievement. Just as he uses yet subverts the visual language of the snapshot, he shoots in a way that suggests effortless, random snapping, but in reality, he works with discipline and intention. His photography is not the product of casual genius, but of deliberate vision and a lot of very hard work. It’s a reminder to all photographers to approach our work with similar intention and discipline. As his friend Stanley Booth says,

“Eggleston is the great photographer that he is because he has worked harder than any 12 people. He’s worked terribly hard and he’s worked terribly smart, always doing things that no one else has done.” (19)

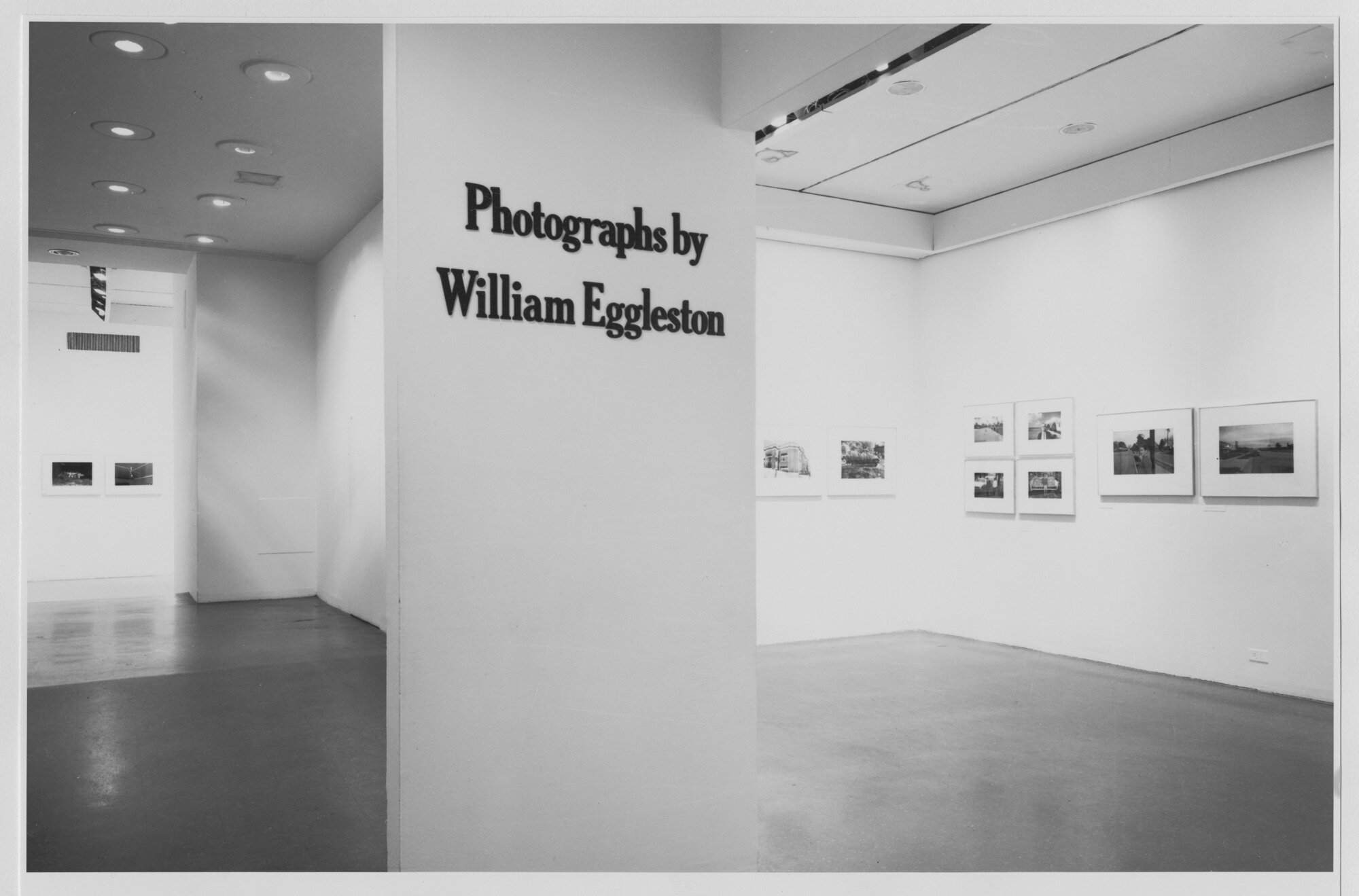

4. Eggleston had the first exhibition of color photographs at MoMA

Photographs by William Eggleston exhibition view at the Museum of Modern Art (1976)

The final misconception I want to discuss is a historical one. It’s the easiest to debunk, yet one of the most pervasive. And I think it’s so ubiquitous because it fits a narrative – of Eggleston as the color pioneer, the undisputed Father of Color Photography. But once again, debunking this myth doesn’t diminish his importance, but it places his achievement in the proper context. There’s no doubt that Eggleston’s 1976 MoMA exhibition Photographs by William Eggleston was a groundbreaking moment in the history of color photography, and in particular for the acceptance of color photography in the fine art world. But many well-respected photographers had been experimenting with color work for decades, and quite a bit of this work had achieved exposure in the museum environment. The first solo exhibition of color photographs at MoMA was actually Eliot Porter’s Birds in Color all the way back in 1943, and the first significant show dedicated to color photography was a survey called Color Photography in 1950, curated by Edward Steichen and including artists such as Ansel Adams, Harry Callahan, Robert Capa, Elliott Erwitt, and even Weegee. Prior to Eggleston, Ernst Haas (1962), Marie Cosindas (1966), and Helen Levitt (1974) all had solo shows of color work there. (20)

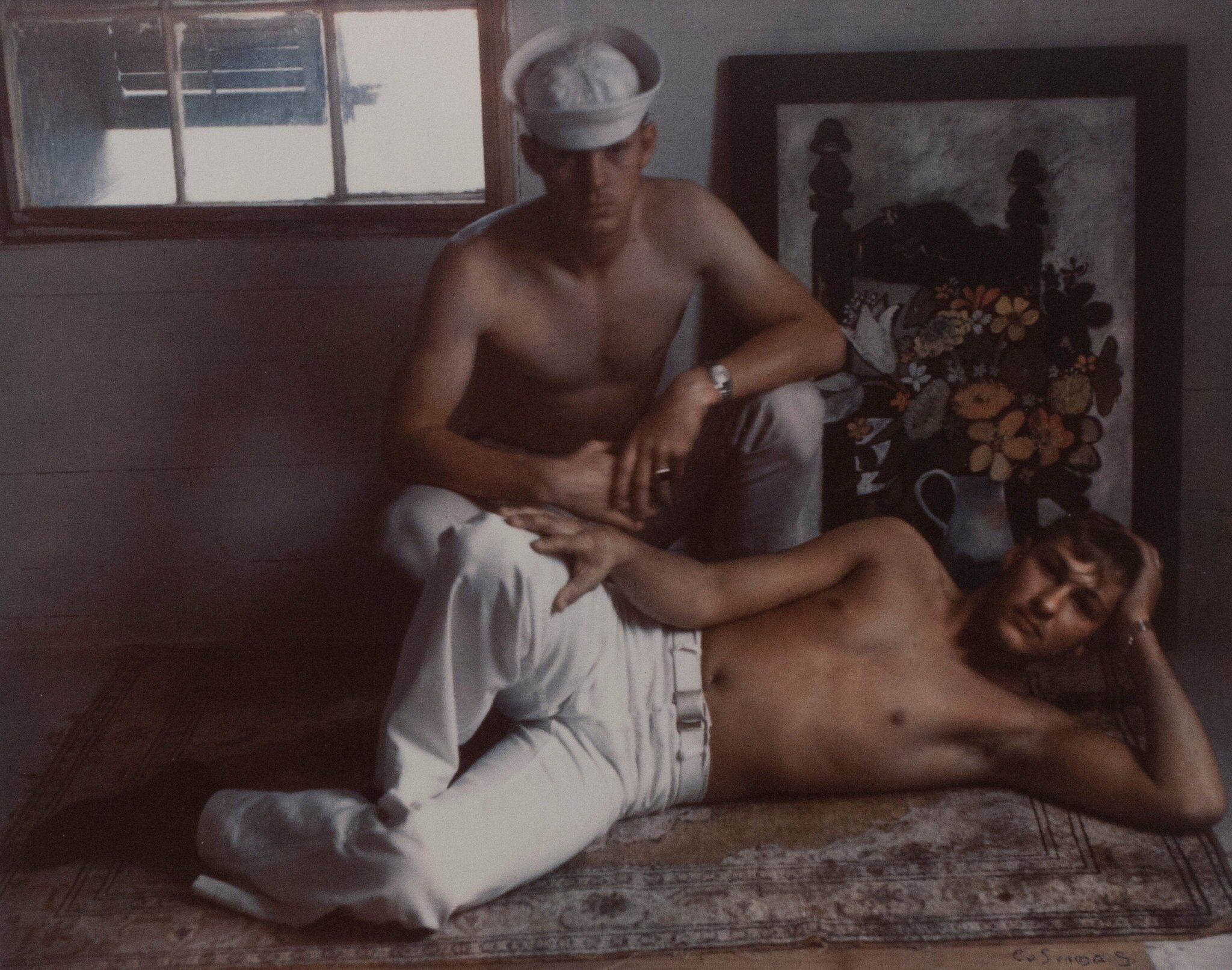

Marie Cosindas, Sailors, Key West (1966)

The idea of Eggleston having the first color museum show isn’t even close to being correct. So why does it persist? A large part of it has to do with the influence of John Szarkowski, the Director of Photography at MoMA from 1962-1991. Although far from a household name even among photographers today, there is perhaps no one who had a greater impact on the understanding of photography in the art world in the second half of the 20th century. Szarkowski was not only a curator, but also a prolific writer and ultimately an influential tastemaker. (21) He aggressively promoted the work of several photographers who would become icons of the medium, particularly Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander, Diane Arbus, and of course Eggleston. He became not only a curator but also their mentor and champion. Simultaneously, his writing, such as the books The Photographer’s Eye (1966) and Looking At Photographs (1973) largely established an accepted lineage of “straight” photography that went from Eugene Atget, through Walker Evans and Robert Frank, and down to these newer practitioners from the 1960s.

And the historical record suggests that it wasn’t so much Eggleston’s photographs, but more Szarkowski’s presentation and marketing of them to the art world, that led to Photographs by William Eggleston being remembered as the breakthrough for color. As suggested in a thesis by Reva Leigh Main:

Eggleston did not change the medium itself, but rather … John Szarkowski’s presentation of the work changed the discourse surrounding color photography to the extent that New York critics effectively copied and pasted Szarkowki’s assessments into their reviews. (22)

William Eggleston’s Guide (1976)

She argues that whereas prior curators such as Steichen had struggled to establish a narrative for color photography – resulting in a mishmash like the 1950 MoMA survey – Szarkowski championed Eggleston because he fit the narrative that Szarkowski had already been pushing, of photography as a “picture making system,” with color as just one of its traits. Returning to the rock star analogy, Szarkowski’s discovery of Eggleston reminds me of Sun Records founder Sam Phillips’ discovery of Elvis Presley. As the legend goes, Phillips wanted to find a white artist who could sing with the feel of the black R&B performers that he had already been recording, resulting in a breakthrough, and a new form of music (at least commercially) – rock & roll. Similarly, Szarkowski found in Eggleston a color practitioner who embodied the aesthetic and value system he had already established around previous artists working in monochrome, resulting in a new form – color art photography.

The available evidence bears this out. Not only did multiple artists have exhibitions of color photography in the years before Eggleston at MoMA and elsewhere, but Eggleston himself was already getting significant attention in the art world in the years prior to the MoMA exhibition. He received a Guggenheim Fellowship grant in 1974 and had his first solo show that same year at the Jefferson Place Gallery in Washington, DC. The following year he received a National Endowment for the Arts Photographic Fellowship and had another solo exhibition at the Carpenter Center at Harvard University. (23) Around the same time, several contemporaries – William Christenberry, for example – had exhibitions of color photography which didn’t seem to be met with any controversy at all.

Moreover, the critical reviews of Photographs by William Eggleston seemed to respond just as much, if not more, to Szarkowski’s presentation of the work than to the photographs themselves. Reviews of the traveling version of the show echoed this, and the importance of Eggleston’s validation by Szarkowski and MoMA. As Main puts it:

… the real significance of Eggleston’s exhibition was the way it stimulated dialogue surrounding color photography as a medium. Many histories of color photography have cited William Eggleston’s 1976 MoMA show as moment that color photography became “accepted” as a form of fine art … The critical backlash that followed the exhibition is often understood as emblematic of the “controversy of color,” showing an American public that was not ready or willing to see a medium with such “low” associations grace gallery walls. However … color was not, in fact, the controversy. In reality, it was Szarkowski’s clearly articulated, largely publicized critical statement … that was the root of the show’s condemnation. Critic’s exclamations were largely reactions against Szarkowski’s designations of Eggleston’s color photographs as “perfect” despite their basic … snapshot appearance. (24)

Untitled, from Troubled Waters (1980)

Ultimately, as documented by many scholars in recent years, the acceptance of color by the art establishment was much more fluid and complex than most people realize, and Eggleston’s MoMA debut was just one episode that led to a growing acceptance – and eventually, by the early 1980s, embrace – of color photography as fine art. And the controversy over his photographs seemed to have been driven far more by Szarkowski’s curatorial presentation – as well as the challengingly banal subject matter and snapshot-like aesthetic of the photographs – than simply their incorporation of color.

* * *

Untitled (c. 1968-74) from Chromes

In the end, William Eggleston will always be somewhat of a mythical figure. If you “get” his pictures, there’s something magical and mysterious about the way he’s able to turn scenes of ordinary life into powerful images imbued with intelligence and cohesion, evocative of vivid emotions and sometimes even sinister undertones.

His famously laconic attitude toward interviews perpetuates the mystery of his genius. But when you scratch the surface, it turns out that he’s actually revealed a great deal more about his interests, motivations, and challenges than might be perceived at first. In dealing with the myths, and taking a deeper dive into what is known about Eggleston and what he’s shared, the perception I come away with about him isn’t that of simply a gifted genius, but instead a driven artist who has worked relentlessly for decades to push the boundaries of his medium and to challenge his own understanding.

For me, especially as a photographer, that reality is far more inspiring than the legend.

1. Kodachrome is a discontinued and now itself somewhat legendary film (what other film stock has a hit song about it?) that was manufactured by Kodak from 1935 to 2009, and for some time it was the only color film available in the US in 35mm format. As opposed to color negative film, which is developed into a negative image and can be readily used to create prints, Kodachrome was a transparency or slide film, meaning that when the film was developed, it formed positive color slides. These were typically projected, but could also be made into prints through a handful of now obsolete processes such as Cibachrome or dye transfer. Kodachrome used a complex and lengthy development process called K-14, and by the end of its run was developed by only one lab in the US. Kodachrome was known for its saturated colors, minimal grain, excellent sharpness and detail, and its longevity and resistance to fading. Slide film in general is known for less grain, higher saturation and a narrower dynamic range (its ability to capture a span of light intensity) than color negative film. It was the dominant type of color film used in many professional applications including landscape and fashion photography. Other slide films besides Kodachrome are still made, but slide film is much less popular and usually more expensive to process than color negative film today.

2. Adam Welch, “Chronology,” in William Eggleston: Democratic Camera Photographs and Video, 1961-2008, ed. Elisabeth Sussman and Thomas Weski (New York: Whitney Museum Of American Art, 2008), 271.

3. Thomas Weski, “I Can’t Fly, But I Can Make Experiments,” in William Eggleston: Democratic Camera Photographs and Video, 1961-2008, ed. Elisabeth Sussman and Thomas Weski (New York: Whitney Museum Of American Art, 2008), 5-6.

4. Stanley Booth, “Triumph of the Quotidian,” in William Eggleston: Democratic Camera Photographs and Video, 1961-2008, ed. Elisabeth Sussman and Thomas Weski (New York: Whitney Museum Of American Art, 2008), 266.

5. Stanley Booth, “Triumph of the Quotidian,” 266.

6. Stanley Booth, “Triumph of the Quotidian,” 267.

7. Joel Meyerowitz, Taking My Time (London: Phaidon Press, 2012), 41.

8. William Eggleston, Memphis, October 2001 in William Eggleston (London: Thames & Hudson, 2002), V.

9. Katherine A. Bussard, “Full Spectrum: Expanding the History of American Color Photography,” in Color Rush: American Color Photography from Stieglitz to Sherman, ed. Katherine A. Bussard & Lisa Hostetler (New York: Aperture Foundation, 2013), 11.

10. Kristine McKenna, “Soaking Up the Local Color: William Eggleston brought color photography into the art world. Now he brings his eye for unlikely beauty to L.A.,” Los Angeles Times, June 5, 1994, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1994-06-05-ca-650-story.html

11. Mark Holborn, “Afterword,” in The Democratic Forest, (New York: Doubleday, 1989).

12. McKenna, “Soaking Up the Local Color.”

13. Thomas Weski, “The Tender-Cruel Camera,” in William Eggleston: The Hasselblad Award 1998, (Gothenburg: Hasselblad Center, 1999).

14. Mark Holborn, “Introduction,” in William Eggleston: Ancient and Modern, (New York: Random House, 1992), 20-21

15. McKenna, “Soaking Up the Local Color.”

16. Sean O’Hagan, “Out of the Ordinary,” Guardian, July 24, 2004, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2004/ jul/25/photography1

17. Imagine, season 13, episode 4, “The Colourful Mr. Eggleston,” directed by Jack Cocker and Reiner Holzemer, written by = featuring William Eggleston, aired July 14, 2009.

18. O’Hagan, “Out of the Ordinary.”

19. Tim Sampson, ‘Eggle Eye’, Memphis Magazine, March 1994.

20. Katherine A. Bussard, “Full Spectrum: Expanding the History of American Color Photography,” in Color Rush: American Color Photography from Stieglitz to Sherman, ed. Katherine A. Bussard & Lisa Hostetler (New York: Aperture Foundation, 2013), 6, 11.

21. Philip Gefter, “John Szarkowski, Eminent Curator of Photography, Dies at 81,” New York Times (New York, NY), July 9, 2007.

22. Reva Leigh Main, Eggleston, Christenberry, Divola: Color Photography Beyond the New York Reception (Riverside: UC Riverside, 2016), 5.

23. Welch, “Chronology,” 272-3.

24. Main, Eggleston, Christenberry, Divola, 96.

Text Copyright © Sebastian Siadecki, 2020.

Images Copyright © William Eggleston, except as indicated.